What I Learned About History And Art In 2024

How one patron at the Cy Twombly exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art took me back 160 years to Paris in a matter of seconds

The Gregorian calendar tells us we're coming up on a milestone—the end of a unit of measurement we call a year—though it has absolutely nothing to do with the position of our planet in the universe, or anything else for that matter.

Or, it sort of does, but it has less to do with astronomical accuracy than it does Pope Gregory XIII wanting Easter to fall upon a preferred date.

Einstein explained to anyone with the mental capacity to at least partially understand his thought process that time is relative. There were others in the rarified academic world of the ultra smarty pants who argued against Einstein, saying that time is just an illusion.

Can you imagine the chutzpah it takes to argue with Einstein!

Whatever your opinion, it’s “time” to look “back”.

Take stock.

Here goes.

There are 31,536,000 seconds in a year. At least that’s what Google tells me in a .5 seconds search retrieval. I could be making a huge blunder and I don’t know why, but I believe Google. If you gave me a minute I could confirm this number on a piece of scratch paper and a pencil, but for our purpose, Google’s calculation is adequate.

It doesn’t matter. It’s all relative. It’s all an illusion. Right?

Of all of those 31.5 million seconds in 2024, about five of them are seared in my brain.

Five seconds was all it took for me to discover the true essence of the history of art.

Those five seconds preserved forever in the amber of my memory occurred on May 30, a little after noontime according to the time stamp on some jpegs I made that day, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s exhibition of Cy Towmbly’s Fifty Days At Illium.

Before I tell you what happened, maybe some need to know a bit about Twombly and his work. I promise in the interest of time that I’ll be brief.

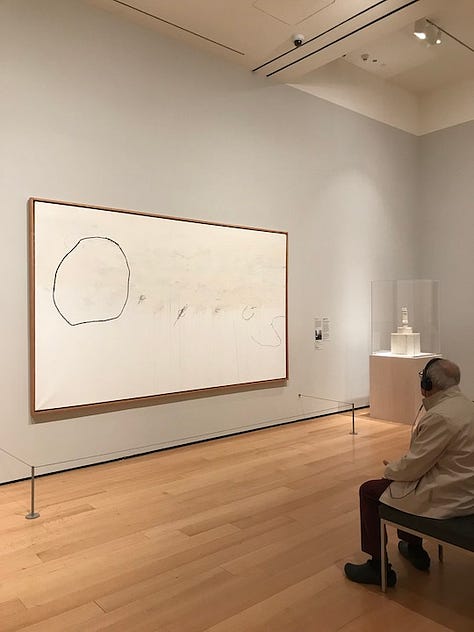

The modernist painter Cy Twombly has always made me smile, even laugh at times. I have to admit that before that day in Philadelphia, I never really understood his work. What he’s known for—large canvases made up of what appears to be doodles set against a neutral ground, never seemed that deep to me. It never convinced me he was investigating anything. Just sort of pulling the wool over the art world’s eyes. Which was part of the reason for my smile: I’ll side with anyone who goes up against the system and wins.

Or at least, fights it to a draw. (Get it? Draw? He’s an artist. Artists draw.)

Never mind.

Anyway.

The Cy Twombly exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts/Boston in 2023 didn’t do anything to dissuade this notion I had. But can I speak freely? (Of course I can! That’s why I get paid the big bucks for writing this blog!) The MFA hardly ever impresses me. It’s more of a mausoleum to art than a real, breathing institution. Except for the rare occasion—Turner’s Modern World in 2022 comes to mind—many times the MFA engages in what Sue frowningly refers to as an intellectual spanking: long on pretension, short on enlightenment.

Still, there was something about his art that I liked, I just couldn’t put my finger on why.

From what I read he was an interesting character. He hung out with Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Motherwell at Black Mountain, and he was friends with Jasper Johns and John Cage. Now there’s a rat pack I would have loved to hang out with.

And he married an Italian baroness. This is serious Netflix biopic material.

It’s just that it didn’t seem to me he was keeping up with the rest of his crew.

Until I saw the exhibit in Philadelphia.

Boom.

And I watched a man walk into the gallery.

Double boom.

To quote Sue again, suddenly I had the keys to the kingdom.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art was exhibiting Twombly’s Fifty Days At Illium in its entirety, ten canvases based on the Illiad hung in order in one gallery, except for the first piece, Shield of Achilles, located right outside the entrance. Kind of like a welcome mat.

Tucked back in a corner of the museum off the beaten path, the space was just the right size and positioned within the overall floor plan of the museum so you automatically were intimate with the entire group of paintings, yet had just enough room for yourself to step away from the artwork.

Intimacy. That’s what you should be looking for when viewing art. Just you and the artwork. One on one.

JSYK, a lot, maybe even most paintings, are meant to be experienced up close, or at least a lot closer than most people view them. Stepping back and looking all intellectual is for poseurs. Don’t be afraid; they’re not going to bite. Get up close in the space where the artist was when the painting was being made and really look at it. Look for brushstrokes and details and the hand of the artist.

It’s a powerful experience to see a group of paintings that a major artist meant to be seen together. So many times we see one-offs. A Rothko here, a Barnett Newman there. If you can see the complete set of Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross you might understand what I mean.

Pro Tip: To really experience art to the point of understanding it, you have to view it multiple times. A couple of years ago in Madrid I viewed Guernica maybe ten individual times. Museum entry fees are expensive, and the way you can afford multiple trips is by buying a year’s subscription to the museum, even if you intend to use it for only a few days. In this case, while Sue and I were traveling, we had bought a year’s membership at the Chicago Art Institute, which, thanks to partnerships, also gets us in for free for a year to the MOMA, MFA/Boston, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art among others.

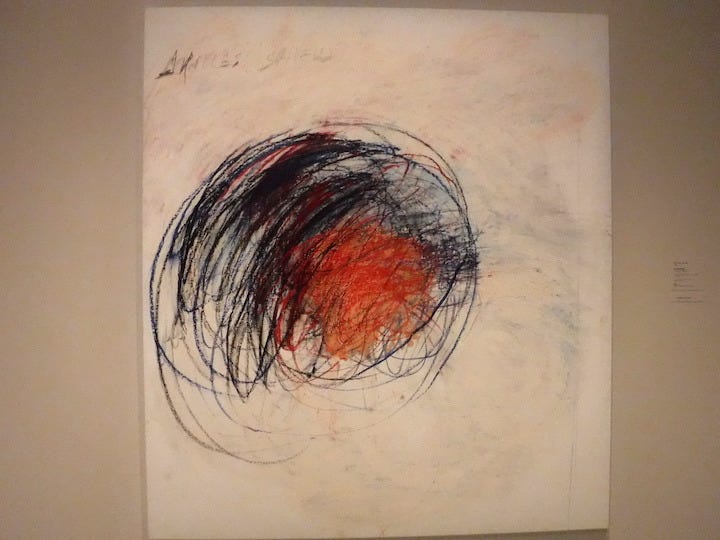

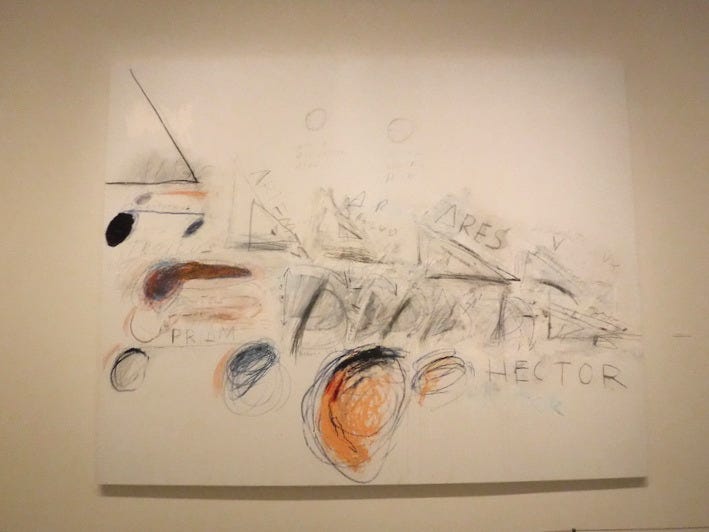

I’m not going to go into Twombly’s interpretation and depiction of the Iliad simply because I know just enough Greek mythology to be dangerous. Twombly was steeped in the Mediterranean world including the ancient Greeks.

And while I wouldn’t know Hector from his horse, I can look at Illians In Battle and clearly see the balance in the composition, how Shield of Achilles, the first piece of the series, is repurposed and acts as a fulcrum for what is in the balance above it.

By the time we reach #8, Twombly is repurposing visual language he established in earlier pieces to tell the story, just as words, phrases, and events establish a narrative in a book. He’s upending traditional narrative.

Why?

Well, I do know enough about text used in art that meaning very often is reduced to having no meaning. There is no meaning attached to text or the order of the letters. To understand that, you need to understand asemic writing, which is writing devoid of meaning.

What is the purpose of words without meaning, you might ask?

Ask yourself if the Egyptians ever foresaw the day when hieroglyphics would be indecipherable? It didn’t happen in a day. Or when an asteroid obliterated their civilization in a moment. It happened over time.

And understand that the day is coming when our written language will be indecipherable, assigned perhaps to the confines of a digital keyboard. If you don’t believe me, remember that cursive writing is not being taught in many schools in the United States anymore. Sometime in the near future, there might documents that the next generation of Americans may not be able to read, like love letter members of their families sent back and forth between home and the fronts of world wars. The Declaration of Independence will be conscripted to scholarly experts. The ones being vilified by MAGAts today, by the way.

Our written language may soon be as indecipherable as Egyptian hieroglyphics. Artists like Twombly were prescient of that, already realizing that words and letters might someday be no more than chicken scratch on a page.

Oh, and that one patron I spoke about? The one who entered the gallery?

Watching people enter a space containing works like Fifty Days In Illium is a fun exercise in people watching. Most seem confused. There is curiosity. The majority seem to want to understand, but most sort of just give up and walk back out again.

Then there was this one man. In a matter of a few seconds he entered the space, took one quick look at the artwork, registered intense anger, spun on his heels, and angrily walked out. I mean, he was personally outraged. He took off like a bottle rocket.

What the…?

And then I remembered. People were outraged by the Impressionists. It seems unbelievable to people today, but in 1863 people not only couldn’t understand Impressionism, but they would be personally outraged by it.

Personally outraged by paintings. Imagine!

Just like that guy in Philadelphia.

I had just witnessed a moment in art history that has been re-enacted time and time again over the centuries. Seeing it actually acted out in an exhibition these days though, was as rare as seeing a unicorn. Or discovering a comet.

And I realized that probably the best lesson I learned about art and art history in 2024 was not coming to an understanding and gaining an appreciation for an artist whose work I had been struggling with for a number of years. And how that understanding then opened up doors to other methods like asemic writing and greater understanding of the use of text in contemporary art.

No. My best lesson of 2024 was watching a man’s reaction to something he didn’t understand, and wasn’t willing to even try to understand. That right there, was the essence of the history of art. That right there was what artists have struggled against and have had to overcome for centuries. That right there was what women artists have struggled with for centuries to reach the measly position they occupy at today’s art world table. What marginalized people have faced when all they wanted was to be heard. Or even just left alone. What any artist who had a vision that butted up against accepted conventions struggled against. Any artist who wanted to do something different.

The status quo.

I hope he chokes on a banana.

Thank you!!! I have always loved Cy Twombly's work, so I was drawn into your essay from the start, and then so pleasantly surprised - this doesn't happen often - when you got to "unicorn" I was like, "no, just anyone beyond the status quo," and then you went there! So thank you! I feel seen. I have always been aware of Twombly as a queer artist and yes, art is always trying to get us to see, and yet so many people refuse the invitation.

Thank you John. So interesting and as you know, I know little about art, however I learn through you. My biggest take away is, I will now always stand where the artist stood while painting to really see what he/she is putting forth. Great writings bro-in-law.